Gregg A. Robbins-Welty, MD MS HEC-C

“That didn’t go well,” I muttered. Deflated, and perhaps indulging in self-pity, I thought I’d done everything right. Yet, I hadn’t connected with the patient the way I wanted. Why do I feel this way? What could I do differently next time? These and other similar questions open the door to understanding the use of psychotherapeutic techniques in palliative care.

Most palliative care specialists (PCS) don’t see themselves as psychotherapists. Images of a Freudian leather chaise lounge and elbow-patched tweed feel worlds away from an intensive care unit or oncology ward. Few PCS have advanced, or even basic, training in psychotherapy. And while there is a growing number of psychiatry-trained PCS, most come from a more traditional, white-coated background.1 Nevertheless, skilled PCS routinely use psychological techniques to forge meaningful connections with seriously ill patients and their families.

Palliative care specialists are trained to be highly observant, attuned to noticing and responding to emotional subtleties. One classic example is avoiding the trap of answering a patient’s emotional plea disguised as a question. I was taught as a medical student, “If you respond to ‘How could cancer have happened to me?’ with a discussion about oncogenes, you’ve missed the boat entirely.” I’m still terrified to discuss oncogenes with patients—but the point is clear: PCS have the instincts to use psychotherapeutic techniques to better understand their patients, ultimately improving outcomes.

One key psychotherapeutic concept that directly applies to palliative care is countertransference. While transference refers to the patient’s feelings projected onto the clinician, countertransference is the clinician’s emotional response to the patient.2 In essence, grasping countertransference requires PCS to use their inherent observational and emotional skills to reflect inwardly.

Countertransference is not only shaped by the clinician’s current relationship with the patient but also influenced by every other relationship they’ve had—extending far beyond the bedside. When two people first meet, there is an immediate rush of initial impressions, many of which are based on intuition and prior experience.3,4 In a clinical space, additional expectations and role responsibilities come into play. Even before the encounter, emotions are likely to surface; mental scaffolding is established, and emotional triggers are set. Influenced by background, early parental relationships, spiritual beliefs, and prior familiarities with grief, PCS enter each encounter with much more than just their clinical expertise.

Countertransference extends beyond our conscious awareness as well. Unspoken feelings may reveal themselves in our actions—perhaps by cutting visits short, avoiding patients with difficult families, or focusing on symptoms alone.4,5 For patients we feel positively toward, we may unintentionally and optimistically overestimate their prognosis. Diving deeply into a patient’s story can uncover our own vulnerabilities. Emotional resonance or dissonance with our own life experiences can complicate our ability to address feelings of sadness, helplessness, or frustration.4 Acknowledging these emotions is crucial, as neglecting them may lead to unproductive disconnection. By recognizing our countertransference, we can transform annoyance or confusion into empathy.

Self-reflection presents its own set of challenges. It requires time and emotional effort, or maybe it was discouraged during training. While completely natural, it can feel uncomfortable not to form an immediate bond with every patient or to find certain interactions less rewarding. Recognizing these feelings—both positive and negative—can enhance our emotional management, improve patient interactions, and in some cases even have diagnostic value. For example, patients with borderline personality disorder often trigger strong emotions in clinicians. Recognizing this countertransference can aid in diagnosis.

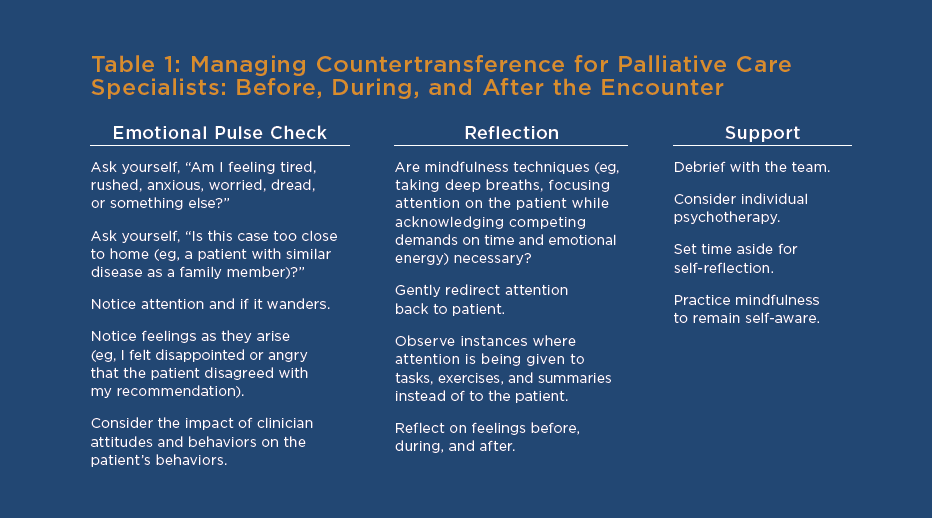

So, how can PCS better understand their countertransference and utilize it to enhance patient outcomes? Table 1 offers some suggestions. Traditional guidance often recommends seeking personal therapy.6 Additional strategies might include consulting with colleagues with psychological expertise about challenging cases, or practicing mindfulness. Mindfulness helps us identify our emotions in real-time—like feeling sadness when a patient reminds us of a loved one. Furthermore, leaning on our interdisciplinary team—social workers, psychologists, and chaplains—can provide valuable support and insights into the complex emotions that arise in end-of-life care.2

The common experience of a visit that “did not go well” is something all PCS can relate to. What could I do differently next time? Introspection is essential.

References

- Shalev D, Brenner K, Carlson RL, et al. Palliative care psychiatry: building synergy across the spectrum. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2024;26(30):60-72. doi:10.1007/s11920-024-01485-5.

- Katz RS, Johnson TA, eds. When Professionals Weep: Emotional and Countertransference Responses in Palliative and End-of-Life Care. New York, NY: Routledge; 2016.

- Boston PH, Mount BM: The caregiver’s perspective on existential and spiritual distress in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32(1):13-26.

- Rosenberg LB, Brenner KO, Jackson VA, et al. The meaning of together: exploring transference and countertransference in palliative care settings. J Palliat Med. 2021;24(11):1598-1602.

- Wilson SN: The meanings of medicating: pills and play. Am J Psychother. 2005;59(1):19-29.

- Riordan P, Briscoe J, Kamal AH, Jones CA, Webb JA. Top ten tips palliative care clinicians should know about mental health and serious illness. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(8):1171-1176.

Gregg Robbins-Welty, MD MS HEC-C is an internist, psychiatrist, ethicist, and palliative medicine fellow at the University of Pittsburgh. He serves as the chair of the AAHPM early career special interest group.